Flight from Tolkemit in West Prussia

Anni Konnegen was born on January 24, 1932, in the small town of Tolkemit in West Prussia on the Vistula Lagoon. She was the youngest daughter of Gehrmann family. On her thirteenth birthday, Anni and her nineteen-year-old sister, Grete, begin their flight from Tolkemit. Both are separated from the family and are not allowed to leave Poland to join their parents in Essenrode until November 1957.

Anni Konnegen has recorded her flight experiences in a book which she begins with the following words:

This book is a journey back into my past… and it tells the sad story of the flight from our beloved home…Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”

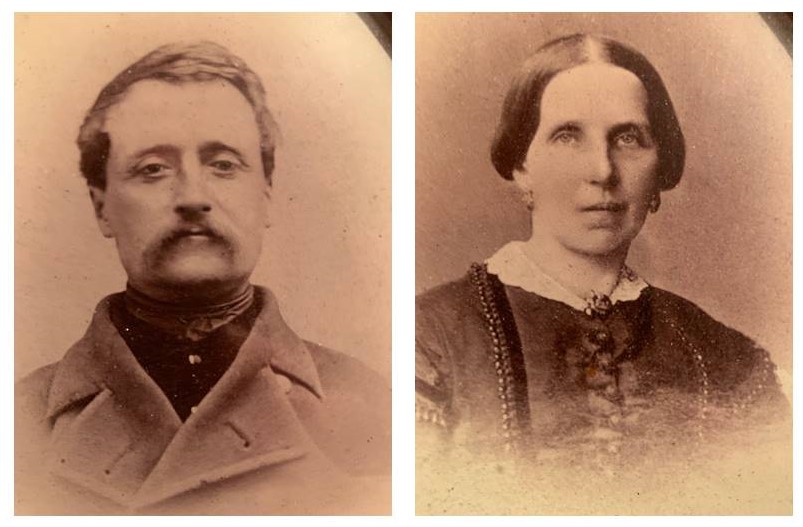

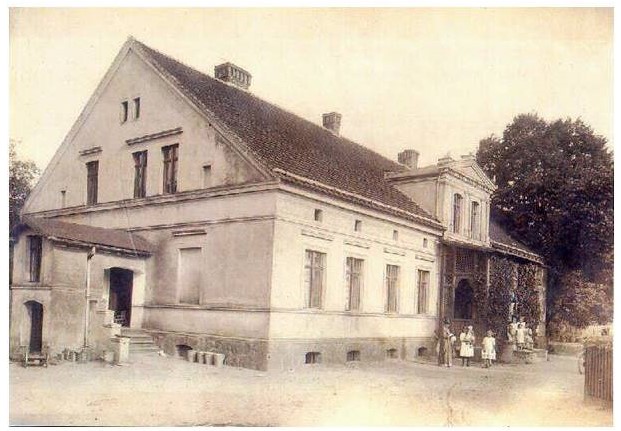

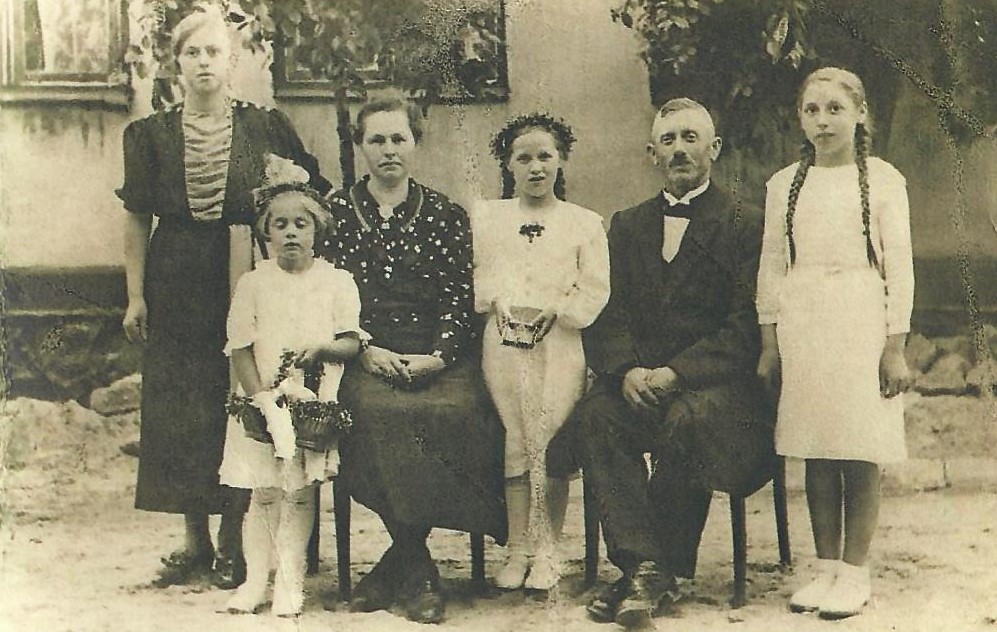

Anni Konnegen is born as the youngest daughter of the Gehrmann family in the small town of Tolkemit in West Prussia on the Vistula Lagoon.

Father Ferdinand works in the brickyard in Panklau. When Anni is eight years old, her mother dies at only 42. Anni’s sister, Grete, now takes over the responsibility for the household and becomes a mother substitute for her younger sister. Until her flight, Anni attends the elementary school in Tolkemit while Grete works in the pottery making “Tolkemiter Erde”.

It was January 24, 1945, my thirteenth birthday. Actually a beautiful day, but it was the day of my flight, the day I had to leave home with my sister Grete, then nineteen years old.

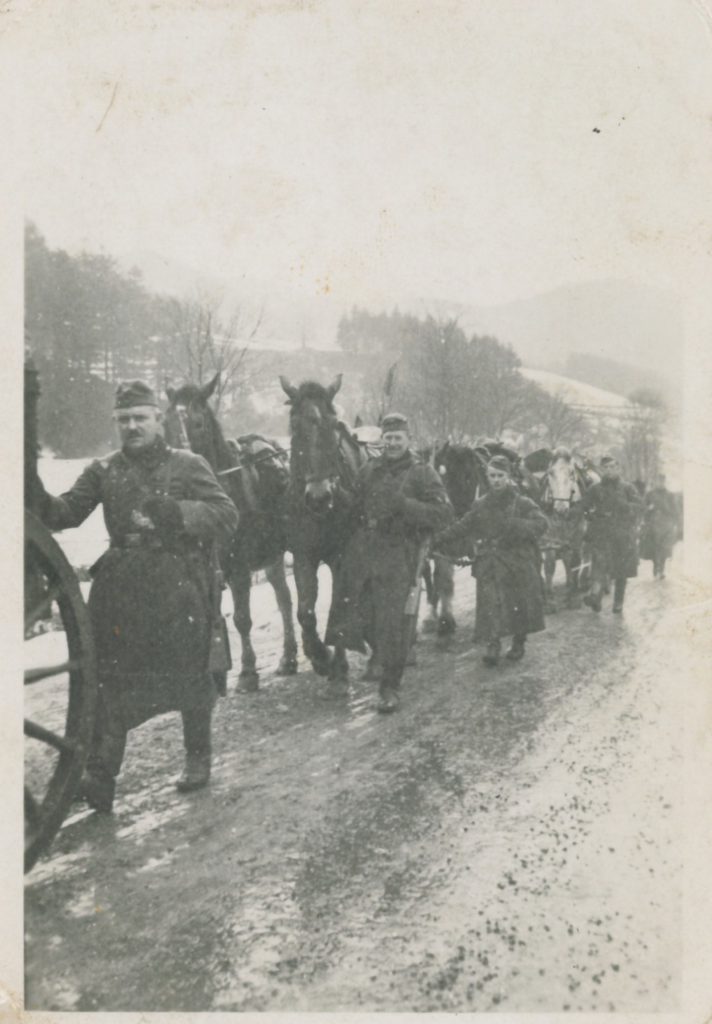

In the afternoon at 3 pm the first arrivals of the Russian Army came from the direction of Elbing and increased immensely in numbers until the evening. The The Russians went into the houses, picked out women and young girls and raped them.

Grete and I hid upstairs in the children’s room when dad came to us and said: ‘Children run!’ So we ran!!!

The Neumann family lived in Frauenburger Strasse. Grete was a friend of their daughter. We could hide there. For two days. Unfortunately we were betrayed and the Russians came and set the house on fire. The front of the house was on fire so we ran out of the back of the burning building. .

All around us only the whistling of the bullets could be heard. We couldn’t wait for our family anymore. They all fled a few days later.

Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”

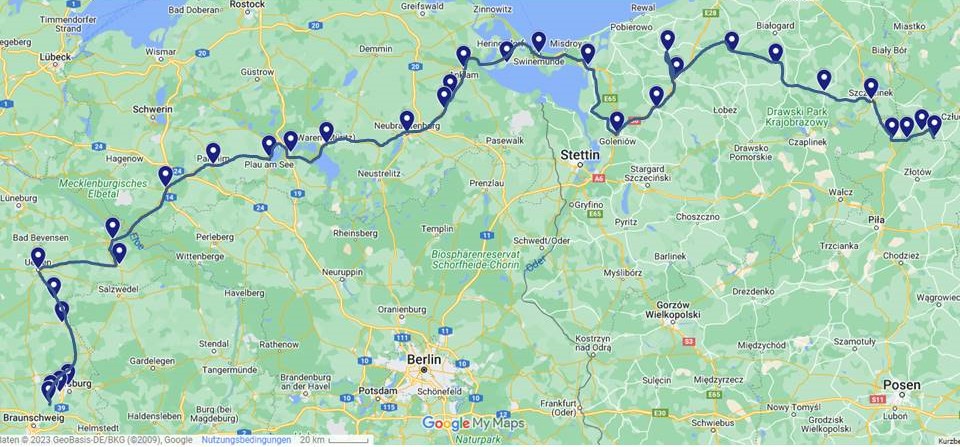

Anni and Grete are separated from their family. After both have been on the road for weeks under the most adverse conditions, their flight to the west fails in March 1945. Like many other refugees, Anni and Grete are overrun by Russian troops. Anni continues to write about this:

Grete and I were all we had left. … My sister fell ill and got dysentery. After Grete’s recovery we got a lodging with farmer Rägger in Wusterwitz, in the district of Schlawe. At that time the month of March had already passed. Wusterwitz was evacuated two or three days later and we went on to Stolpe. … There again, a few days later, it was “Save yourself who can.” The bridges were blown up. Again we ran! Alone! Always to where there were many people … until we arrived in Starnitz.

In Starnitz we stayed in school for a while. But already we were under Russian supervision and the locals did not welcome us. There I got dysentery and typhoid. Grete was kidnapped and made to work dismanting the railway tracks, so that now I was left all alone. Strangers took care of me a little.

After a few weeks Grete came back and we found an empty room with two beds and bench next to a stove in Starnitz where we took shelter for a good year.Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”

Anni and her sister find work on an estate in Gottberg. While Grete works, Anni looks after Russian children. At first everything is still under Russian administration. Anni continues:

Now I had to get food and went begging and hoarding. A few farm wives would often give me a pot of gruel for Grete and me. . .

While Grete was working, I looked after the Russians’ children. So I got a small meal a day and a boy always shot sparrows for me to eat. …Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”

In the summer of 1945 Tolkemit was reassigned under the Potsdam Agreement. Together with all of Hinterpommern, all of West Prussia and the southern half of East Prussia, it was placed under Polish administration and received the Polish name Tolkmicko.

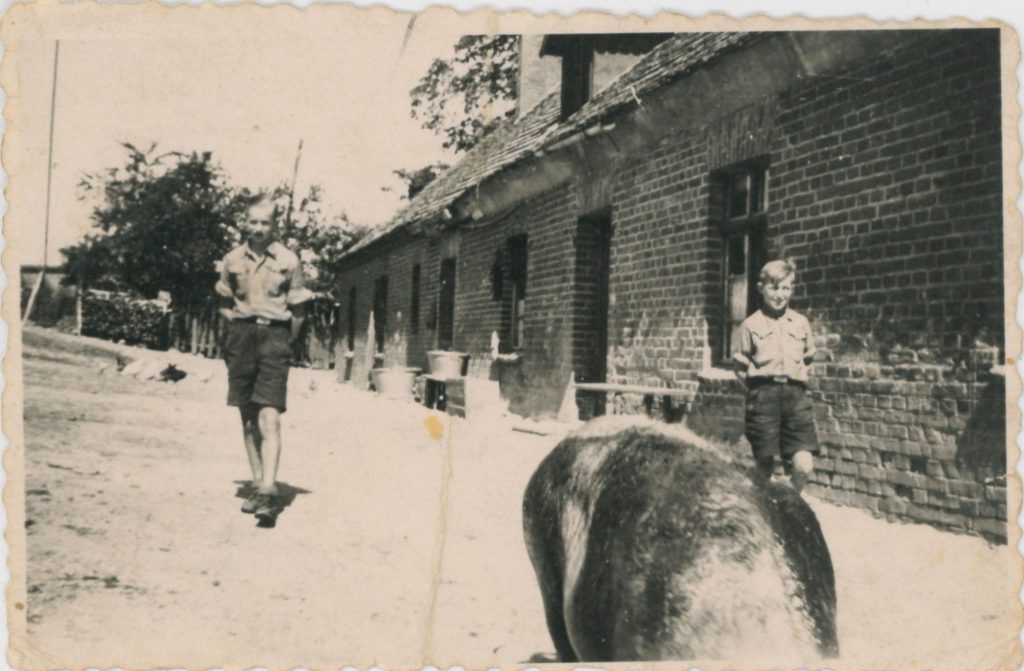

At the Gottberg estate Anni meets her future husband, Erwin Konnegen. His flight from East Prussia had also ended here and he got a job as a tractor driver.

On October 9, 1954, we married and Erwin moved in with us. After the wedding I stopped working on the estate and we started our own cattle farm. Erwin and Grete worked on the farm and I took care of the household and cattle, which gave me a lot of pleasure. We had sheep, pigs, goats, chickens and geese. There was a lot to do…Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”

1955 Anni and Erwin have a son, Wilfried, and 1957 a daughter, Marlis, is born. Anni has now started her own family and together with her husband and sister has created a good basis for her life. Nevertheless, the desire and longing to return to her parents remains.

Despite these positive events, we continued to work obtaining on our exit permit to Germany all these years. Starnitz remained under Russian supervision from 1945 to 1949 and has been part of Poland since 1949.

In 1956 we were told to become Polish, which we did not want, because we wantedt to join our parents in Germany. Finally, we were allowed to leave Poland at the beginning of November 1957.Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”

Anni and her family spend one night in the transit camp at Friedland near Göttingen. The next day Anni’s father picks her up from there. The joy is great on both sides! Anni later describes her arrival in Essenrode as follows:

Only four days after our arrival, Erwin started work. Lene’s husband Erich had arranged a job for him at VW in Wolfsburg, which he retained until his retirement, just like Grete. Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”

After more than twelve years of separation from parents and family, arriving in Essenrode was not as easy as hoped. Even though the joy of being reunited as a family in one place was enormous, the newcomers faced quite a few challenges.

Nevertheless a difficult time began for us! Christmas came and we had nothing. We did not get any support from the church or community. Not even a helping hand was given to us. Yes, these Christmases were the worst and I wished I could go back to Poland. In Poland we would have had everything by now. During that time I cried a lot and said again and again: ‘If only we had stayed with the Polish.’

Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”

But Anni and her family do not give up. After the separation from their parents, a terrible flight and the loss of all their belongings, they had already faced and mastered a total new beginning. Did they have enough strength and would it also succeed a second time?

So we had to start all over again in Essenrode! Bit by bit we had to rebuild everything. I worked on the estate of Baron von Lüneburg [the estate owner] to earn some extra money.

Yes, this is how we managed to save money and became builders in 1969. We built ourselves a beautiful house in a new housing estate in Essenrode. So in the autumn of 1970 we were proud homeowners.

So everything went back on track. Wilfried and Marlis grew up, went to school and then both were almost into apprenticeship, when something small announced itself to us. In May 1971, our baby Sabine was born. Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”

Anni Konnegen is always drawn to Tolkemit on the Vistula Lagoon. Numerous visits with her children, relatives and friends lead her back to her homeland time and again. Anni Konnegen concludes her memories of flight with the following words:

Time passed and over the years we had created a new “home” for ourselves in Essenrode. There were good times, as well as not so good times.

But my “Heimat” will always be East Prussia.Anni Konnegen in “Ostpreußen – meine Heimat mein zuhaus”